“China has an overall goal . . . to become the leading country in the world, the wealthiest country in the world and the most powerful country in the world,” President Biden said in his first press conference in March 2021. “That’s not going to happen on my watch.”

If you hadn’t noticed, we’ve entered a new Cold War – and technology is at the heart of it.

At the same press conference, Biden also told his audience: “I predict to you, your children or grandchildren are going to be doing their doctoral thesis on the issue of who succeeded: autocracy or democracy?”

Meanwhile Biden’s infrastructure plan states frankly in its opening paragraph that it’s designed to help “position the United States to out-compete China.” And the UK government’s integrated review of security, defence and foreign policy for the next decade prioritises “improving our ability to respond to the systemic challenge that China poses to our security, prosperity and values.”

Conversely, “China is betting that the West is in irreversible decline”, The Economist wrote in April. “China is now applying calculated doses of pain to shock Westerners into realising that the old, American-led order is ending.”

Welcome to Cold War II

This is what the historian Niall Ferguson calls “Cold War II”. Western countries have woken up to the rise of China and the fact that it creates a clear danger to their hegemony in global trade and politics for the rest of the 21st century. But why does this matter to the tech sector?

The strategic lever in any war is the control of resources. In Cold War I, during the second half of the twentieth century, that was about the oil, coal and gas that fuelled economies and armies, and, to a lesser extent, the mass media that informed the public. Control those, and you were hard to beat.

But in Cold War II, the strategic resources are technology – the internet, chips, data, telecoms networks, AI and more. That’s because this technology controls economic value today, as well as more and more aspects of society’s infrastructure.

How it all began

We’ve already seen the early skirmishes of the tech-focused Cold War II. President Trump came into power in 2017 having made China his public enemy number one. But he didn’t attack them by banning their oil companies or financial services firms. He clamped down on Chinese tech firms – first Huawei, and then TikTok and Xiaomi. He blocked investment, disrupted supply chains and scuppered efforts at growing in the US market. He was trying to strangle these Chinese tech brands to death and maintain American superiority.

The pandemic in 2020 probably accelerated the beginnings of Cold War II as well. In the space of a year, the number of Americans who thought that China was their number one global adversary went from 22 per cent to 45 per cent.

A clash between China and the West was probably inevitable at some stage this century, because of the Thucydides Trap – the historical fact that tension (and usually war) is always generated between the existing hegemon and the rising power.

Obama in the US and Cameron in the UK tried to avoid that trap – or at least put it off – by binding China into the global economic order. Trump’s election scuppered that approach and his provocative behaviour probably just brought the inevitable clash forward a decade or so.

The implications for tech

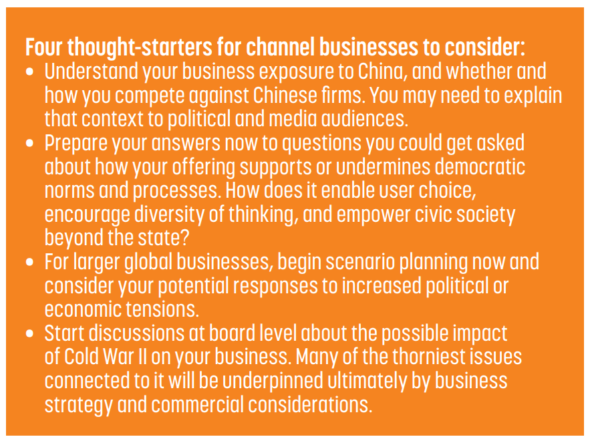

But here we are, at the start of Cold War II. What does it mean for the tech sector? It feels inevitable that Western tech companies will be recruited into this fight, just as aerospace, industrial and energy companies were during Cold War I. Tech companies are the Boeing, Dow Chemical and Shell of Cold War II. That’s a fundamental shift for businesses who’ve prided themselves on their careful political neutrality for the past few decades.

It puts geopolitics much higher up the agenda for vendors, MSP and resellers. They’ll need to show how they are playing their part in this global struggle. They’ll also have to prove that they encourage freedom rather than, say, tracking our data or deploying algorithms that inhibit our choices. This will generate tough choices and ethical dilemmas – like whether to get involved in military and governmental contracts.

These implications won’t hit most tech companies immediately, of course. Cold War II is still in its nascent stages. But if history is anything to go by, Cold War II is likely to be with us for decades.